|

|

|

|

|

This article may be reprinted free of charge provided 1) that there is clear attribution to the Orthomolecular Medicine News Service, and 2) that both the OMNS free subscription link http://orthomolecular.org/subscribe.html and also the OMNS archive link http://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/index.shtml are included. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

The Transformative Effects of High-Dose Thiamine Therapy: Dr Derrick Lonsdale's Legacy

by Elliot OvertonDr. Derrick Lonsdale, a true luminary in the field of nutritional medicine, passed away last year at the ripe old age of 100 years old. Beginning his career as a pediatrician at the Cleveland clinic, he dedicated nearly five decades to uncovering the profound impact of high-dose thiamine (vitamin B1) on chronic disease. He was a vocal proponent of the orthomolecular approach to medicine, and tirelessly sought to raise awareness of what he referred to as high-calorie malnutrition-a state where an abundance of processed foods depletes essential micronutrients, impairing metabolism at a fundamental level and setting the stage for chronic health conditions.

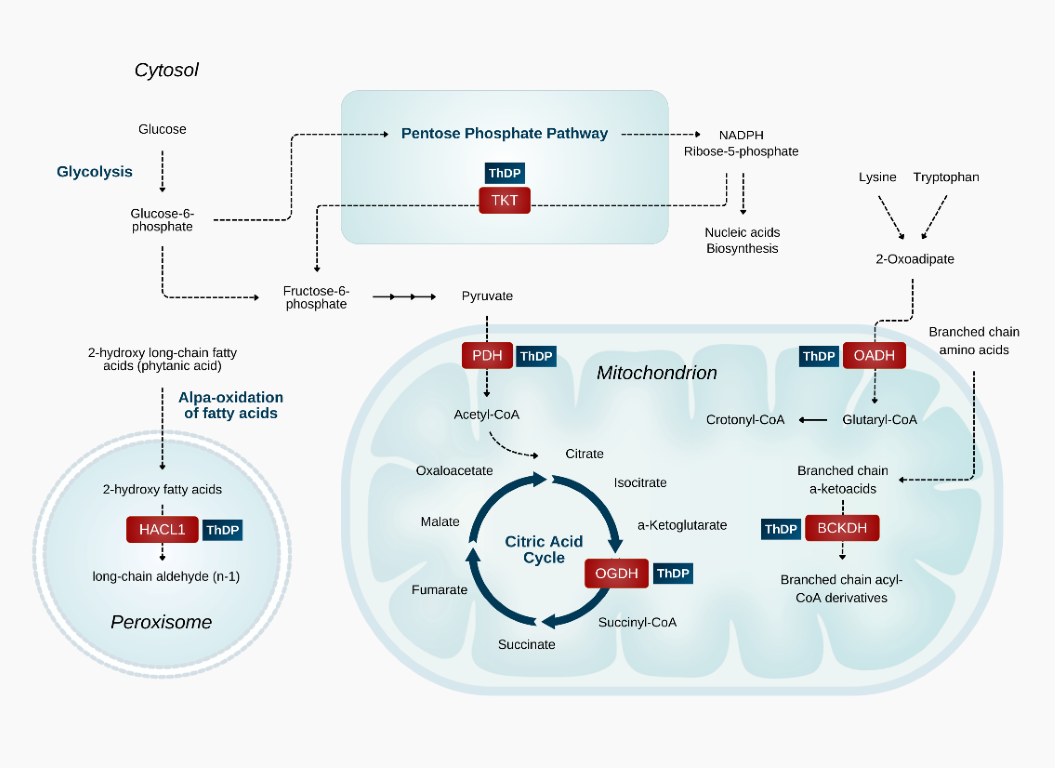

Furthermore, his pioneering work challenged conventional medicine's narrow view of vitamin deficiency, revealing that pharmacological doses of thiamine may achieve far more than merely prevent deficiency-they can actively restore energy metabolism. Dr. Lonsdale often referred to this nutrient as the "spark of life" and "gateway to energy metabolism," emphasising its vital role in counteracting the metabolic stressors of modern life when administered in appropriate amount. He introduced the concept of thiamine dependency-the state where some individuals require supraphysiological doses on a consistent basis to maintain health-an insight that may be highly relevant to many modern chronic diseases. Remarkably, much of what he hypothesized decades ago is now being validated by cutting edge research, demonstrating that his intuitive sense was accurate. Yet, despite his extensive research and clinical contributions, thiamine remains one of the most overlooked nutrients in medicine today. Even after seven years of applying these principles, I am still astounded by the transformative effects this vitamin can have in such a broad range of health problems. In the sections that follow, we will explore thiamine's essential role in bioenergetics, its unique anti-stress properties, and the overlooked concept of organ-specific localized deficiency-an emerging phenomenon that may be crucial for specific health conditions, particularly neurodegenerative disease. We will also examine the rationale behind using pharmacological doses as a powerful therapeutic intervention for a wide array of modern diseases. Thiamine: A Universal "Anti-Stress" MoleculeThiamine (also known as vitamin B1) is an essential vitamin naturally found in a variety of whole foods, especially meats and organs, legumes and whole grains. Due to its hydrophilic nature and short half-life, it requires continuous dietary replenishment. Its widespread role in human physiology centres on its participation as an essential cofactor for enzymes involved in various biochemical pathways. Among these, thiamine-dependent dehydrogenases are uniquely positioned at key metabolic cross-points, enabling cellular metabolic flexibility and modulating the global rate of energy metabolism. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH), the rate-limiting enzyme for mitochondrial glucose oxidation, bridges glycolysis and the TCA cycle, rendering thiamine indispensable for efficient utilization of carbohydrate. Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase (KGDH), another rate-limiting enzyme of the TCA cycle, links bioenergetics, amino acid metabolism, and neurotransmitter synthesis. Beyond the generation of NADH and disposal of glutamate, KGDH acts as a metabolic "signaling hub," influencing redox balance, growth, the hypoxic response, protein signaling, and calcium homeostasis (1).

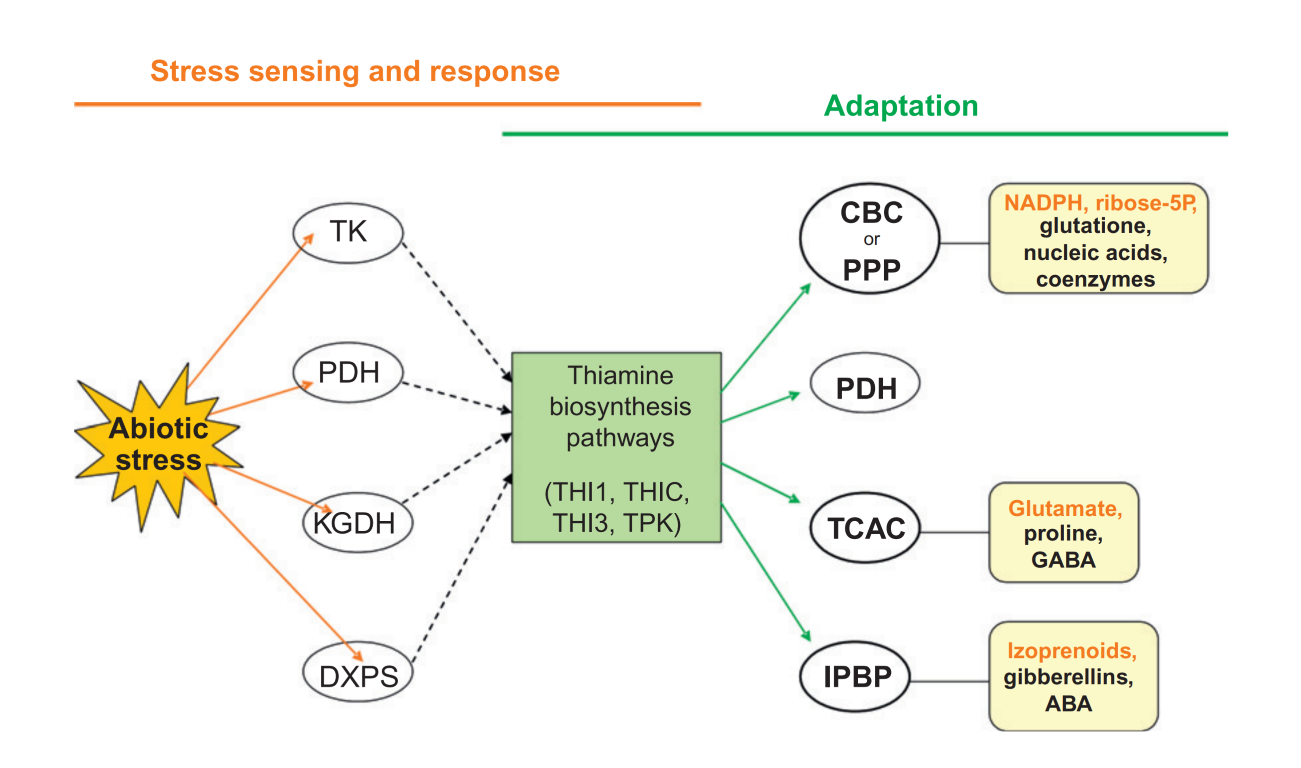

The unique positioning of these rate-limiting thiamine-dependent enzymes at critical junctures in metabolism means that they are tasked with governing the global rate of ATP production. For this reason, intracellular thiamine levels are also tightly coupled to mitochondrial oxygen utilization. Insufficient thiamine levels disrupt this process, leading to pseudohypoxia-a state in which cells cannot utilize oxygen despite adequate availability, leading to widespread energy deficit. This connection is evidenced by the striking resemblance between the histological changes observed in thiamine-deficient brains and those seen in hypoxic injury (2-4). Both conditions activate the same coordinated cellular response to stress, marked by the stabilization and activation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) (5-7). Additionally, both hypoxia and thiamine deficiency were shown to upregulate SLC19A3, a membrane-bound thiamine transporter, presumably as a compensatory mechanism to enhance thiamine uptake into the cell for the purpose of stress mitigation. Consistent with these findings, a decline in thiamine status correlates with hypothermia and and a marked reduction in oxidative metabolic rate in animals (8). Furthermore, in was shown to produce identical symptoms those found in Hans Selye's model of "The General Adaptation Syndrome" (9). Reflecting this tight-knit relationship between thiamine, bioenergetics, and adaptation to stress, Dr. Lonsdale aptly referred to thiamine as "the spark of life" and "the gateway to energy metabolism." Thiamine's anti-stress properties also appear to be conserved across plants, fungi, and bacteria. The nutrient has been referred to as an "environmental stress protectant" and "stress alarmone" (10) in plants. Under conditions of biotic and abiotic stress, plants are known to increase their production of thiamine and upregulate thiamine-dependent enzymes as a means of improving resilience in the face of unfavorable environmental conditions. Furthermore, exogenous thiamine confers resistance against many different types of disease (11).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123864796000044 For bacteria, similar upregulation of genes involved in thiamine biosynthesis occurs in cyanobacteria under stress (12), and E. coli were found to "accumulate large amounts of thiamine triphosphate, a thiamine derivative, under severe energy stress (13). In yeast, thiamine also confers protection against oxidative, osmotic, and thermal stress (14). From a broad perspective, it would appear that thiamine exhibits distinctive "anti-stress" properties and can enhance cellular resilience across diverse biological systems. Recognizing these qualities can provide a solid foundation for understanding how and why thiamine might be so useful in mitigating the impact of chronic health conditions which are characterized by metabolic, oxidative, and environmental stressors. "The Great Imitator": The Many Faces of DeficiencyA severe deficiency in this nutrient is classically know to result in thiamine deficiency disorders (TDDs), which predominantly affect one or more of three major body systems: The central nervous system (causing Wernicke encephalopathy), the cardiovascular system (causing Wet Beriberi), and the peripheral nerves (leading to Dry Beriberi). The classic pattern of symptoms depends on the subtype and can include, but is not limited to, ataxia, opthalmoplegia, peripheral neuropathy, paresthesia, vertigo, vascular insufficiency, edema, and even heart failure. However, micronutrient status should best be understood as existing on a continuum, rather than as a clear-cut binary divide between 'sufficiency' and 'deficiency.' The latter view is overly simplistic and fails to capture the complex and progressive effects that insufficiency can exert on human physiology. Evidence shows that even marginal deficits in thiamine can manifest in subtle yet significant ways, negatively impacting metabolism and organ function long before overt deficiency disorders are diagnosed. Given the ubiquity of thiamine-dependent enzymes and their governing role in energy metabolism, it is conceivable that sufficiency and/or impaired utilization of thiamine could therefore impact any cell, tissue and organ which requires ATP. Indeed, nearly a century's worth of research has demonstrated that even mild insufficiency can manifest in a broad array of non-specific symptoms that extent well beyond the classic spectrum of TDDs. Given thiamine's central role in energy metabolism, organs with the highest demand for energy are the most vulnerable, with many associated symptoms reflecting some degree of autonomic dysfunction. Lonsdale himself spearheaded the treatment of dysautonomia (of various kinds) with thiamine derivatives (15-17), based on the principle that it could address disturbed bioenergetics in the limbic/brainstem regions of the brain involved in modulation of the autonomic nervous system. In his own words: "Beriberi is the prototype for functional dysautonomia in its early stages." (16). He described the brain as becoming "hyper-irritable" under oxidative stress, leading to exaggerated autonomic nervous system responses to even minor stimuli, such as changes in weather or exposure to air conditioning. Indeed, signs and symptoms of dysautonomia are remarkably prevalent among all of the established TDDs (18-21), and in my own experience, thiamine can be the single most effective treatment for such conditions. Clinical manifestations range from mild to severe, and can also fluctuate based on season, physical activity level, and other environmental factors. Furthermore, they can be non-specific and therefore difficult to pinpoint in clinical practice. The general and non-specific nature of symptoms was illustrated as early as 1940 in one of the first ever studies on experimental deficiency in human subjects (22). Remarkably, classical signs of beriberi were virtually absent for the majority of the study period (88 days). Instead, the researchers documented a broad range of symptoms pertaining to every body system, many of which fall under the modern diagnostic umbrella of dysautonomia. These symptoms included: Fatigue upon mild exertion, tachycardia, pseudoangina, irregular heart rate, pallor, blushing, hyperhidrosis, temperature dysregulation, genitourinary paresthesia, frequency of micturition, shortness of breath, vertigo, impaired glucose tolerance, insomnia, along with mood disturbances and poor concentration. General malaise, heavy sensation in the lower extremities, loss of strength, chest tightness, diminished visual acuity and restlessness. Abdominal distension, belching, and alternating constipation and diarrhea, achlorhydria or hypochlorhydria, delayed gastric emptying, and reduced intestinal motility. These broad and often nebulous symptoms observed in thiamine insufficiency highlight the challenges involved in accurate identification, and no doubt contributes to its misdiagnosis. Many of these manifestations are subtle, easily overlooked, and commonly misattributed to other conditions, which leads to widespread under recognition. In reality, thiamine insufficiency develops insidiously, raising an important question: Could a significant portion of the population be affected without realizing it? Thiamine Insufficiency: A Hidden Epidemic

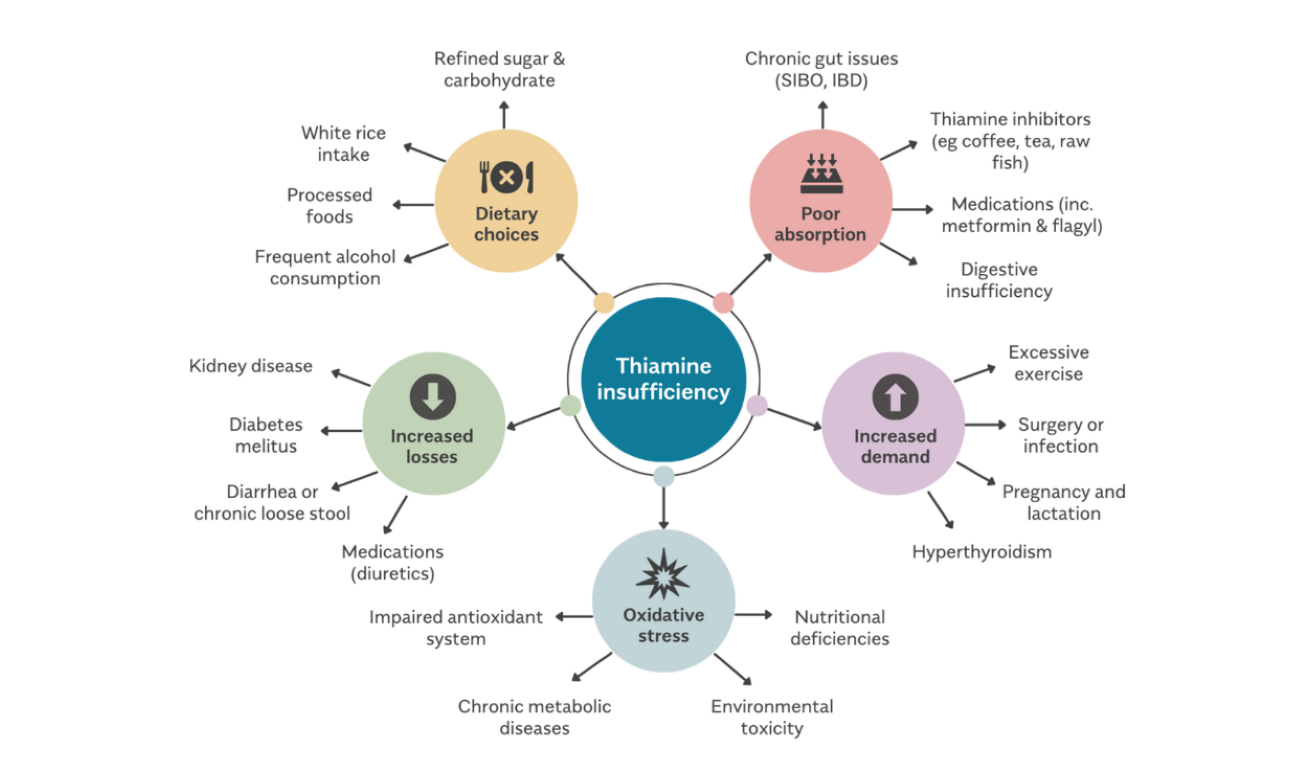

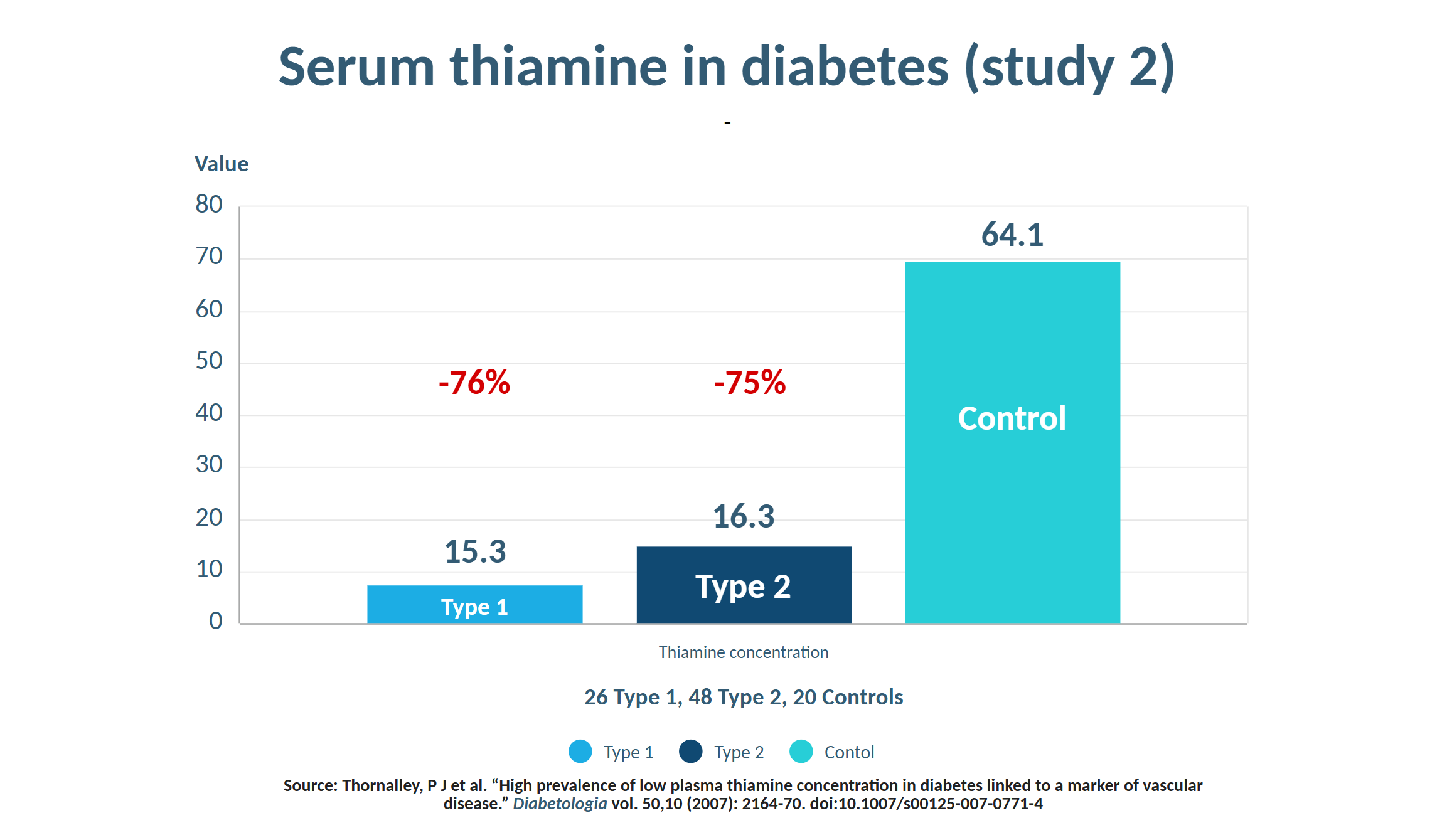

Outside of the context of specific comorbidities such as alcoholism (23), malabsorptive syndromes (24), and eating disorders (25), frank deficiency widely considered rare in developed nations, with the prevailing assumption that food fortification has largely eradicated it. A closer examination of the evidence, however, suggests otherwise. Insufficiency is, in fact, far more prevalent than commonly recognized (26), with some studies showing occurrence between 20-50% in psychiatric (27) and elderly populations (28,29). Plasma thiamine levels were up to 76% lower in type 1 and type 2 diabetics (30). Even severe cases of Wernicke Encephalopathy are frequently underdiagnosed (31). Furthermore, testing methods are woefully inadequate for assessing intracellular thiamine status (32). Perhaps the primary driver of widespread deficiency is the occurrence of "high-calorie malnutrition", a term popularized by Lonsdale describing the overconsumption of processed foods rich in calories but devoid of micronutrients, which progressively depletes the body's reserves. This is especially relevant in the modern world, given that consumption of ultra-processed foods has risen substantially in recent decades (33) and now accounts for 50-60% daily caloric intake in some high-income countries (34).

Thiamine status is largely influenced by carbohydrate intake, which necessitates a proportional dietary supply to match metabolic demands (35). In other words, the overconsumption of sugar-laden foods and refined starches naturally places a large burden on the body's thiamine reserves. One of the most striking examples of thiamine's importance comes from the historical epidemic of beriberi in Asia, where populations who were reliant on polished white rice (devoid of thiamine-rich husks) were the first to suffer from severe deficiency. However, another insidious driver is the widespread consumption of oxidized, PUFA-rich industrial seed oils, as demonstrated by a recent study effect (36). Although the exact mechanism wasn't elucidated, research suggests that oxidized breakdown products of PUFAs, such as malondialdehyde, can negatively impact thiamine status in several ways (37,38). Additionally, there are many pharmaceutical drugs which also display potent anti-thiamine effects, such as metformin (39), metronidazole (40), diuretics (41), and omeprazole (42) among several others (43). Dysbiotic changes to the gut microbiome (44), along with stressors of various kinds can also be responsible for reducing thiamine status (45). However, the complexity of this issue extends beyond simple deficiency. In fact, a significant portion of patients who present with thiamine-responsive health conditions may not even have insufficient systemic levels of thiamine. That is, despite "normal" circulating thiamine levels, functional impairment at the cellular or enzymatic level may still justify supplementation with high doses. This emerging area of research, which I find particularly fascinating, challenges the conventional paradigms of nutritional status and highlights the need for more nuanced understanding of nutrient handling and nutritional therapy as a whole. Beyond Addressing Deficiency: Localized or Functional Impairments in Thiamine UtilizationDr. Derrick Lonsdale often emphasized that high-dose thiamine functions as a pharmacological agent rather than merely a nutritional supplement. The doses required to achieve therapeutic effects-often hundreds or even thousands of times the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA)-far exceed what is needed to correct a simple nutritional deficiency, and for prolonged periods of time. In his own words, high-dose thiamine could "coerce energy metabolism back to life," acting as a metabolic stimulant of sorts. The Pharmacological Action of ThiamineThis concept is perhaps best illustrated in examples of inborn errors of metabolism, such as thiamine-responsive maple syrup urine disease, Leigh's disease, methylmalonic academia, homocysteinuria, and other hereditary vitamin-responsive disorders. In these conditions, genetic mutations reduce the affinity of vitamin-dependent enzymes for their respective vitamin cofactor, leading to severe metabolic dysfunction. Mega-doses of the nutrient are required to saturate cells, and compensate for these enzymatic defects, effectively restoring function despite the genetic abnormality (46). While rare, I suspect that similar principles may apply to a much broader range of modern diseases involving enzymatic inactivation or inhibition of vitamin-dependent pathways. This inactivation can occur independently of genetic predisposition and may result from environmental toxins, xenobiotics, chronic inflammation, or oxidative stress. In the context of thiamine-responsive conditions, the issue is not a simple deficiency of thiamine intake but rather defective intracellular handling of thiamine or a functional blockade of thiamine-dependent enzymes, which happen to be uniquely sensitive to such insults (47). There are numerous factors unrelated to dietary intake that have this effect, including:

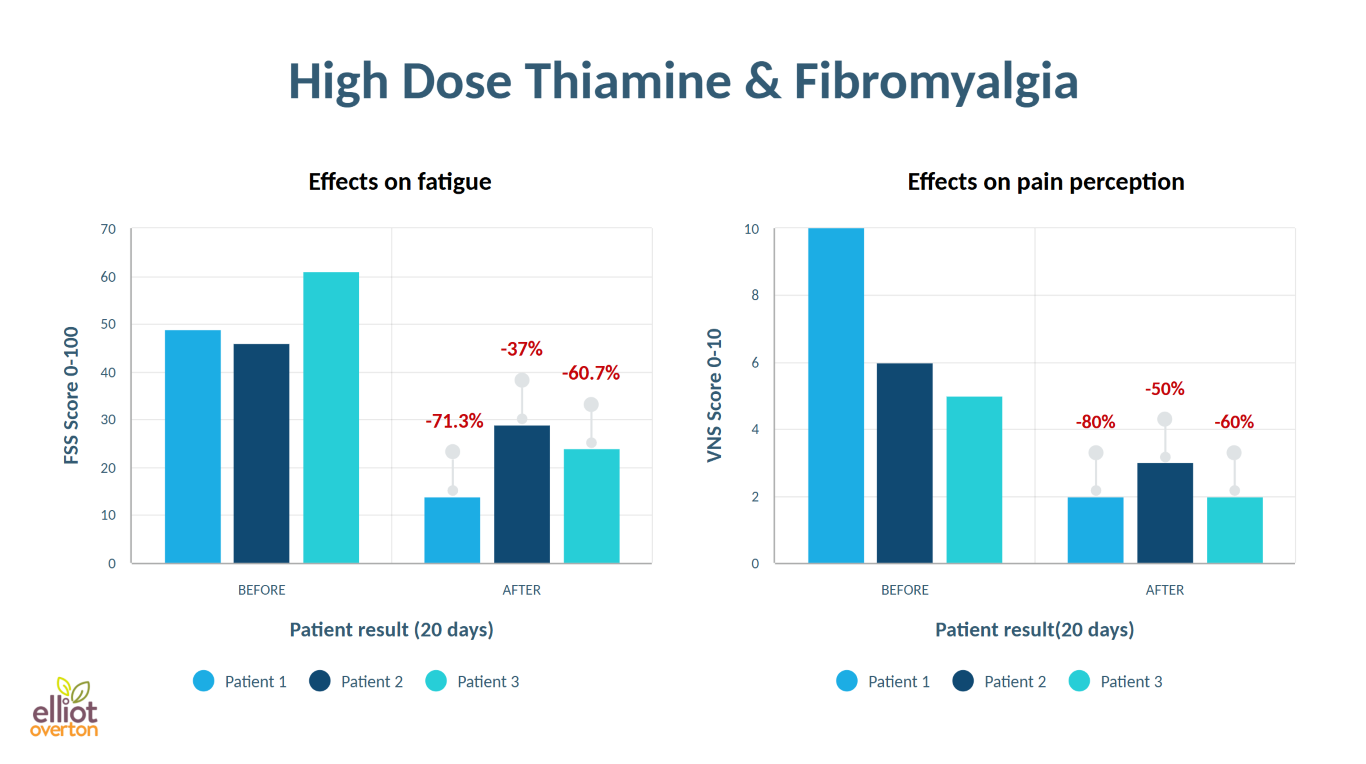

Although temporary enzymatic inhibition may serve normal physiological roles, chronic inhibition is increasingly recognized to be a key driver of pathology (54,55), particularly in the context of neurodegenerative disease. The cumulative effect is mitochondrial dysfunction and a resulting bioenergetic deficit, which triggers a cascade of metabolic impairments that ultimately contribute toward tissue and organ dysfunction. Localized "Deficiency" in Specific Organs & TissuesThe inhibition or "blockade" of thiamine-dependent, rate-limiting enzymes of involved in energy metabolism can mimic the consequences of a systemic nutritional deficiency, but may instead be restricted to specific tissues. Emerging evidence supports the concept of localized thiamine deficiency various tissues and organs, including the brain, heart, pancreas, and even intestine. For this reason, thiamine can be considered a metabolic stimulant, as high-dose administration has the capacity to restore energy metabolism when cells become saturated, via bypassing or overriding metabolic blocks imposed by enzymatic inhibition. In essence, this perspective shifts the focus beyond from merely correcting dietary deficiency to addressing localized dysfunction and enzyme inhibition, potentially offering new therapeutic possibilities for a wide range of chronic conditions. Another important consideration is that tissues with high metabolic demand -particularly in the context of chronic injury or infection- can rapidly deplete their thiamine reserves in response to stress. Such is another scenario that can potentially lead to localized deficiency, in the absence of systemic signs, symptoms, and/or diagnostic tests. Transcriptomic data (forthcoming publication) supports this notion, revealing distinct metabolic abnormalities, including long-term alterations thiamine-dependent enzymes, in enterocytes up to 9 months after gastric bypass surgery. It is conceivable that such changes could occur in practically any cell, tissue or organ exposed to chronic injury, and should therefore be considered in our approach to managing chronic illness. Furthermore, genetic factors undoubtedly play an important role. Abnormalities in genes encoding proteins involved in the transport, activation, and utilization of thiamine could render an individual more susceptible even to minor fluctuations in thiamine status. Such genetic differences may also help to account for some individuals respond favorably to this therapy, while others do not. Keys to Neurodegeneration: Untapped potential for the aging brain?These mechanisms are particularly relevant in the field of neurodegeneration, where decades of research highlight a strong link between disrupted thiamine homeostasis and neurodegenerative processes. Notably, dysfunction of thiamine-dependent enzymes appears to be a hallmark feature of several neurodegenerative conditions, suggesting that localized thiamine dysfunction may be a key contributor to CNS vulnerability and disease progression. Alzheimer's Dementia (AD)A "localized deficiency" of thiamine in the brain has been proposed as a defining characteristic of AD (56), and is known to independently cause many of the key pathological changes including: impaired glucose metabolism (57), neuroinflammation (58), neuron loss (59), impaired cholinergic function (60) and greater presence of amyloid plaques and tangles (61). Disruptions of cerebral thiamine homeostasis and glucose metabolism have been identified (62), and activity of three thiamine-dependent enzymes are reduced in the brain (63,64). One of those is KGDH, whose activity is reduced by as much as 57% (65,66) which occurs in both genetic (67) and sporadic (68) forms of AD. Furthermore, Thiamine transporters decline (69) and metabolic impairments in the brain are closely related to TPP levels (70). Furthermore, levels of active TPP were significantly reduced in the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortex in frontotemporal dementia (71) at autopsy. The synthetic thiamine derivative benfotiamine has been shown to counteract many of the pathological drivers of AD and cognitive decline (72), and a $45 milllon trial is currently underway in AD patients (73). Parkinson's DiseaseEndogenous neurotoxic metabolites associated with PD, such as MPP+ and isoquinolones, are potent inhibitors of thiamine-dependent enzymes (74), Numerous studies have identified KGDH as a key pathological target in Parkinson's disease (PD) (75). KGDH activity is greatly reduced in the substantia nigra (76), with the degree of inhibition correlating with the severity of neurodegeneration (77). Additionally, PD is associated with significant reductions in PDH activity (78,79). Free thiamine concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid were also found to be lower than controls (80). Although there are only two small trials using pharmacological doses of thiamine for PD, the results are extremely promising (81,82). In one of those reports, patients with a milder phenotype achieved complete clinical remission with thiamine therapy. Today, there is an online network of thousands who are self-treating with this approach and are witnessing great benefits. According to the author of the case reports: "It is reasonable to infer that a focal, severe thiamine deficiency due to a dysfunction of thiamine metabolism could cause selective neuronal damage in the centres that are typically hit in this disease. Injection of high doses of thiamine was effective in reversing the symptoms, suggesting that the abnormalities in thiamine-dependent processes could be overcome by diffusion-mediated transport at supranormal thiamine concentrations." The Cholinergic SystemAlthough widespread deficits to the cholinergic system are a well-recognized pathological hallmark of AD, similar -or even more severe- deficits may also occur in PD, albeit in different regions of the brain (83,84). These shared mechanisms may help to further shed light on why thiamine holds significant therapeutic potential. Thiamine is inherently pro-cholinergic, playing a crucial role in acetylcholine (ACh) function at multiple levels. An intimate relationship between thiamine and cholinergic neurotransmission stems from both its coenzyme and non-coenzyme roles. A well-documented consequence of thiamine deficiency is reduced ACh synthesis (60), partly due to the direct role of pyruvate dehydrogenase in supplying acetyl-CoA, the essential precursor for ACh. Additionally, the distribution of acetyl-CoA and its supply for ACh synthesis is also governed by KGDH through its regulation of the TCA cycle, which further links thiamine homeostasis with cholinergic function. However, beyond its metabolic role as a coenzyme, thiamine is essential for axonal membrane excitability and neuronal action potentials (85). Phosphorylated thiamine derivatives regulate ACh neurotransmission (86) and are involved in synaptic function (87,88). Synaptic co-release of thiamine and ACh, with thiamine facilitating neurotransmission, has also been found (89-92). At high concentration, thiamine binds to nicotine ACh receptors (93), while the synthetic thiamine derivatives TTFD and sulbutiamine demonstrate pro-cholinergic effects in multiple studies (94,95). Given these diverse mechanisms, thiamine likely exerts its neuroprotective action through a combination of coenzyme and non-coenzyme effects, further cementing its role as a promising candidate for supporting neurodegenerative states which involve cholinergic decline. Huntington's DiseaseInhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase (96,97) and KGDH (98) have been found. A decrease in thiamine content of the cerebrospinal fluid was shown to precede the onset of motor symptoms (99). Abnormal thiamine metabolism has been found in HD animal models (100), and a recent study identified impaired thiamine transport as a potentially treatable cause of HD. More specifically, abberant polyadenylation of thiamine transporters (SLC19A3) were identified in HD, accompanied by low striatal content of active thiamine in both humans and animals. Supplementation with high dose thiamine combined with biotin improved radiological, motor and neuropathological phenotypes in the animal model (101), and human studies are currently underway (102). Amyotrophic Lateral SclerosisThe frontal cortext in ALS displays substantially lower levels of TPPase, the enzyme which activates thiamine to thiamine pyrophosphate (103), and patients exhibit decreased thiamine derivatives in the cerebrospinal fluid (104). The morphological signatures of Wernicke Encephalopathy have been reported in ALS (105). A case study using high dose benfotiamine (a thiamine derivative) showed promising results in ALS patient (106). Likewise, high doses of another derivative named dibenzoylthiamine normalized the metabolome and lead to improvements in all physiological parameters, motor function and muscle atrophy in an animal model of ALS (107). A series of case reports by Dr Antonio Costantini showed positive responses to high-dose thiamine (HDT) treatment in various other neurological conditions such as dystonia and spinocerebellar ataxia (108), along with a case report on fibromyalgia which showed up to 70% improvement in fatigue and 80% reduction in pain scores (109). Such findings could potentially be explained by dysfunctional thiamine utilization reported in this condition, evidenced by a significantly elevated TPP effect for transketolase (110), and low TPP levels (111), along with low thiamine binding affinity was observed for PDH (112) and transketolase (113).

Collectively, these findings suggest that dysfunction of thiamine-dependent enzymes and/or defects in thiamine metabolism, utilization, or transport may extend far beyond conventional associations, playing a significant role in the pathophysiology of diseases which not traditionally associated with TD. Leveraging Thiamine as a "Cell Protectant"As discussed thus far, evidence strongly supports thiamine's role as a protective agent against mitochondrial impairment. Notably, these benefits are not strictly limited to the correction of a deficiency in the traditional sense, but rather through optimizing key metabolic pathways to maintain energy metabolism. However, it's important to mention that these effects are not limited to neurodegeneration but may also apply to injury various kinds. Dr Victoria Bunik and her team at the Belozersky Institute of Physicochemical Biology in Moscow have extensively studied the effects thiamine in various models. Their research demonstrated that pre-treatment with pharmacological doses of thiamine provided significant neuroprotection and largely mitigated damage in an animal model of traumatic brain injury (114). Following injury, mitochondrial ATP production was preserved, accompanied by vast reductions in glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity along with improvements in neuroinflammation. The proposed mechanism of protection was pharmacological activation of KGDH by thiamine. To quote the authors: "The impairment of OGDHC [KGDH] plays a key role in the glutamate mediated neurotoxicity in neurons during TBI; pharmacological activation of OGDHC [KGDH] may thus be of neuroprotective potential. " The same team later reported similar results in model on spinal trauma, where thiamine was shown to preserve glutathione levels and ameliorate the effects of excess nitric oxide (115). Once again, the mechanism of neuroprotection was thiamine's activation of KGDH, which preserved mitochondrial function and maintained generation of ATP. Indeed, many other studies have highlighted similar protective effects of thiamine (116). Pre-treatment with thiamine pyrophosphate preserved cardiac function via maintaining ATP production in another model of ischemia (117). Thiamine preserved PDH activity in animals post-cardiac arrest (118). Likewise thiamine was also protective in a model of copper toxicity, once again through preventing the inactivation of PDH (119). Beyond these protective roles, thiamine also improves markers of metabolic dysfunction and glucose metabolism improves markers of metabolic dysfunction (120) while exerting anti-fatigue effects, largely by attenuating ATP depletion in skeletal muscle during workload-induced fatigue (121). Beyond Metabolic Support: Thiamine's Non-Coenzyme Protective EffectsThe benefits extend beyond thiamine's function as a coenzyme, because there are a range of non-coenzyme effects which may further contribute to its ability to protect cells and tissues from damage.For example, thiamine pyrophosphate has been shown to shield the liver from cisplatin toxicity protected rat liver (122), and prevented ischemia-related infertility prevented infertility (123). While thiamine itself has demonstrated comparable efficacy to N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (123) in protecting against acetaminophen-induced liver damage. Additionally, cells were safeguarded radiation-induced genetic damage (124), and both thiamine and benfotiamine could counteract ultrasound-induced aggression and oxidative stress while normalizing AMPA receptor expression and plasticity markers in animal studies (125). High-dose thiamine also alleviates biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in models of lead toxicity (126), and pretreatment protected cardiomyocytes from hypoxia-induced apoptosis and DNA fragementation (127). Honoring Dr. Lonsdale's Legacy by Advancing Thiamine Therapy: A New FrontierMany of Dr. Lonsdale's theories on thiamine's mechanisms and therapeutic potential continue to be validated by cutting-edge research. As someone deeply inspired by his work, I have spent the past seven years studying and applying high-dose thiamine in clinical practice, and its effects continue to astound me. I have witnessed remarkable improvements in patients-many without classical risk factors for deficiency-experiencing chronic fatigue, brain fog, fibromyalgia, autonomic dysfunction, functional gut disorders, mood imbalances, and more. Yet, despite its profound impact, thiamine remains largely overlooked, even within functional and alternative medicine circles. In the time I have spent using and learning about this nutrient, my observations have aligned with those of Dr. Derrick Lonsdale, who long recognized that high-dose thiamine does more than correct a dietary deficiency-it reactivates energy metabolism in ways conventional medicine has yet to fully grasp. For decades, Lonsdale tirelessly worked to raise awareness, but conventional medicine failed to listen. Though I was never fortunate enough to meet him in person, we exchanged many emails, and I can attest that he closely followed the scientific research right into his final year. His dedication is evident in his extensive body of work, including Thiamine Deficiency Disease, Dysautonomia, and High-Calorie Malnutrition, co-authored with Dr. Chandler Marrs. So as we continue to explore the implications of his research, we honor his legacy-a testament to the profound effects that nutrients can have in restoring health. In his own words: "We're using the vitamin as a drug and coercing the energy metabolism back into life." About the author:Elliot is a naturopathic nutritionist with additional training through A4M's fellowship program in Anti-Aging, Metabolic, and Functional Medicine. His primary research area focuses on the underlying mechanisms and clinical application of high-dose thiamine (vitamin B1) derivatives. As a speaker, he regularly lectures at professional events to advance the understanding and therapeutic use of thiamine in pharmacological doses for a host of chronic disease states including neurodegeneration, functional GI disorders, and complex conditions such as CFS and fibromyalgia. Through education and advocacy, Elliot aims to make this knowledge accessible to both practitioners and the general public. He is the co-founder of the nutraceutical company Objective Nutrients, runs the YouTube channel "EONutrition" and also manages the website thiamineprotocols.com. Elliot is a member of the Board of Editors of the Orthomolecular Medicine News Service. References:1. Hansen GE, Gibson GE. The α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex as a Hub of Plasticity in Neurodegeneration and Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23:12403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232012403 2. Vortmeyer AO, Hagel C, Laas R. Hypoxia-ischemia and thiamine deficiency. Clin Neuropathol (1993) 12:184-190. 3. Johkura K, Naito M. Wernicke's encephalopathy-like lesions in global cerebral hypoxia. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas (2008) 15:318-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2006.10.022 4. Vortmeyer AO, Colmant HJ. Differentiation between brain lesions in experimental thiamine deficiency. Virchows Arch A (1988) 414:61-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00749739 5. Valle ML, Anderson YT, Grimsey N, Zastre J. Thiamine insufficiency induces Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α as an upstream mediator for neurotoxicity and AD-like pathology. Mol Cell Neurosci (2022) 123:103785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2022.103785 6. Zera K, Zastre J. Thiamine deficiency activates hypoxia inducible factor-1α to facilitate pro-apoptotic responses in mouse primary astrocytes. PLOS ONE (2017) 12:e0186707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186707 7. Sweet RL, Zastre JA. HIF1-α-mediated gene expression induced by vitamin B1 deficiency. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Int Z Vitam- Ernahrungsforschung J Int Vitaminol Nutr (2013) 83:188-197. https://doi.org/10.1024/0300-9831/a000159 8. Langlais PJ, Hall T. Thiamine deficiency-induced disruptions in the diurnal rhythm and regulation of body temperature in the rat. Metab Brain Dis (1998) 13:225-239. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023276009477 9. Some Specific and Non-Specific Effects of Thiamine Deficiency in the Rat. - Floyd R. Skelton, 1950. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3181/00379727-73-17729 [Accessed February 20, 2025] 10. Rapala-Kozik M. "Vitamin B1 (Thiamine).," In: Rébeillé F, Douce R, editors. Advances in Botanical Research. Biosynthesis of Vitamins in Plants Part A. Academic Press (2011). p. 37-91 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386479-6.00004-4 11. Ahn I-P, Kim S, Lee Y-H. Vitamin B1 functions as an activator of plant disease resistance. Plant Physiol (2005) 138:1505-1515. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.104.058693 12. Upregulation of thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis gene upon stress application in 13. Gigliobianco T, Lakaye B, Makarchikov AF, Wins P, Bettendorff L. Adenylate kinase-independent thiamine triphosphate accumulation under severe energy stress in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol (2008) 8:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-8-16 14. Wolak N, Kowalska E, Kozik A, Rapala-Kozik M. Thiamine increases the resistance of baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae against oxidative, osmotic and thermal stress, through mechanisms partly independent of thiamine diphosphate-bound enzymes. FEMS Yeast Res (2014) 14:1249-1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1567-1364.12218 15. Lonsdale D, Nodar RH, Orlowski JP. The Effects of Thiamine on Abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Potentials. J Adv Med (1998) 11:199-207. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023344513264 16. Lonsdale D. Exaggerated Autonomic Asymmetry: A Clue to Nutrient Deficiency Dysautonomia. (2011) https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Exaggerated-Autonomic-Asymmetry%3A-A-Clue-to-Nutrient-Lonsdale/2f66f5baa669933fed0b4e23fb2bac616f2c558e [Accessed February 20, 2025] 17. Lonsdale D, Nodar RH, Orlowski JP. Brainstem dysfunction in infants responsive to thiamine disulfide: preliminary studies in four patients. Clin EEG Electroencephalogr (1982) 13:82-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/155005948201300203 18. Shible AA, Ramadurai D, Gergen D, Reynolds PM. Dry Beriberi Due to Thiamine Deficiency Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy and Wernicke's Encephalopathy Mimicking Guillain-Barré syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep (2019) 20:330-334. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.914051 19. Lonsdale D, Marrs C. Thiamine-Deficient Dysautonomias. Elsevier (2018). p. 161-211 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-810387-6.00005-8 20. Reuler JB, Girard DE, Cooney TG. Current concepts. Wernicke's encephalopathy. N Engl J Med (1985) 312:1035-1039. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198504183121606 21. Branco de Oliveira MV, Irikura S, Lourenço FH de B, Shinsato M, Irikura TCDB, Irikura RB, Albuquerque TVC, Shinsato VN, Orsatti VN, Fontanelli AM, et al. Encephalopathy responsive to thiamine in severe COVID-19 patients. Brain Behav Immun - Health (2021) 14:100252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100252 22. Williams RD. Observations on induced thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency in man. Arch Intern Med (1940) 66:785. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1940.00190160002001 23. Laforenza U, Patrini C, Gastaldi G, Rindi G. Effects of acute and chronic ethanol administration on thiamine metabolizing enzymes in some brain areas and in other organs of the rat. Alcohol Alcohol Oxf Oxfs (1990) 25:591-603. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045055 24. Oudman E, Wijnia JW, Oey MJ, van Dam M, Postma A. Wernicke's encephalopathy in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Nutrition (2021) 86:111182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111182 25. Winston AP, Jamieson CP, Madira W, Gatward NM, Palmer RL. Prevalence of thiamin deficiency in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord (2000) 28:451-454. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4<451::aid-eat14>3.0.co;2-i 26. Marrs C, Lonsdale D. Hiding in Plain Sight: Modern Thiamine Deficiency. Cells (2021) 10:2595. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10102595 27. Carney MW, Ravindran A, Rinsler MG, Williams DG. Thiamine, riboflavin and pyridoxine deficiency in psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci (1982) 141:271-272. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.141.3.271 28. Kwok T, Falconer-Smith JF, Potter JF, Ives DR. Thiamine status of elderly patients with cardiac failure. Age Ageing (1992) 21:67-71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/21.1.67 29. Nichols HK, Basu TK. Thiamin status of the elderly: dietary intake and thiamin pyrophosphate response. J Am Coll Nutr (1994) 13:57-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1994.10718372 30. Thornalley PJ, Babaei-Jadidi R, Al Ali H, Rabbani N, Antonysunil A, Larkin J, Ahmed A, Rayman G, Bodmer CW. High prevalence of low plasma thiamine concentration in diabetes linked to a marker of vascular disease. Diabetologia (2007) 50:2164-2170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-007-0771-4 31. Kohnke S, Meek CL. Don't seek, don't find: The diagnostic challenge of Wernicke's encephalopathy. Ann Clin Biochem (2021) 58:38-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563220939604 32. Whitfield KC, Bourassa MW, Adamolekun B, Bergeron G, Bettendorff L, Brown KH, Cox L, Fattal‐Valevski A, Fischer PR, Frank EL, et al. Thiamine deficiency disorders: diagnosis, prevalence, and a roadmap for global control programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2018) 1430:3-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13919 33. Monteiro CA, Moubarac J-C, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes (2013) 14 Suppl 2:21-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12107 34. Cordova R, Viallon V, Fontvieille E, Peruchet-Noray L, Jansana A, Wagner K-H, Kyrø C, Tjønneland A, Katzke V, Bajracharya R, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a multinational cohort study. Lancet Reg Health - Eur (2023) 35: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100771 35. Elmadfa I, Majchrzak D, Rust P, Genser D. The Thiamine Status of Adult Humans Depends on Carbohydrate Intake. Int J Vitam Nutr Res (2001) 71:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1024/0300-9831.71.4.217 36. Leano J, Raut G, Martinez-Lomeli J, Chen G, Luna C, Degnan P, Curras-Collazo M, Sladek F, Deol P. Vitamin B1 Supplementation Ameliorates Obesogenic Effects of a High Fat Diet in Male Mice. Physiology (2024) 39:1230. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.2024.39.S1.1230 37. Vuorinen PJ, Rokka M, Ritvanen T, Käkelä R, Nikonen S, Pakarinen T, Keinänen M. Changes in thiamine concentrations, fatty acid composition, and some other lipid-related biochemical indices in Baltic Sea Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) during the spawning run and pre-spawning fasting. Helgol Mar Res (2020) 74:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10152-020-00542-9 38. Lukienko PI, Mel'nichenko NG, Zverinskii IV, Zabrodskaya SV. Antioxidant properties of thiamine. Bull Exp Biol Med (2000) 130:874-876. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02682257 39. Liang X, Chien H-C, Yee SW, Giacomini MM, Chen EC, Piao M, Hao J, Twelves J, Lepist E-I, Ray AS, et al. Metformin Is a Substrate and Inhibitor of the Human Thiamine Transporter, THTR-2 (SLC19A3). Mol Pharm (2015) 12:4301-4310. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00501 40. Hassan M, Awadalla E, Ali R, Fouad S, Abdel-Kahaar E. Thiamine deficiency and oxidative stress induced by prolonged metronidazole therapy can explain its side effects of neurotoxicity and infertility in experimental animals: Effect of grapefruit co-therapy. Hum Exp Toxicol (2020) 39:834-847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327119867755 41. Katta N, Balla S, Alpert MA. Does Long-Term Furosemide Therapy Cause Thiamine Deficiency in Patients with Heart Failure? A Focused Review. Am J Med (2016) 129:753.e7-753.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.01.037 42. Nixon PF, Diefenbach RJ, Duggleby RG. Inhibition of transketolase and pyruvate decarboxylase by omeprazole. Biochem Pharmacol (1992) 44:177-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(92)90053-l 43. Karadima V, Kraniotou C, Bellos G, Tsangaris GTh. Drug-micronutrient interactions: food for thought and thought for action. EPMA J (2016) 7:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13167-016-0059-1 44. Costliow ZA, Degnan PH. Thiamine Acquisition Strategies Impact Metabolism and Competition in the Gut Microbe Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. mSystems (2017) 2:e00116-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00116-17 45. Attaluri P, Castillo A, Edriss H, Nugent K. Thiamine Deficiency: An Important Consideration in Critically Ill Patients. Am J Med Sci (2018) 356:382-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2018.06.015 46. Ames BN, Elson-Schwab I, Silver EA. High-dose vitamin therapy stimulates variant enzymes with decreased coenzyme binding affinity (increased K(m)): relevance to genetic disease and polymorphisms. Am J Clin Nutr (2002) 75:616-658. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/75.4.616 47. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci (2005) 360:2335-2345. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1764 48. Mailloux RJ, Bériault R, Lemire J, Singh R, Chénier DR, Hamel RD, Appanna VD. The Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle, an Ancient Metabolic Network with a Novel Twist. PLOS ONE (2007) 2:e690. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000690 49. Bergquist ER, Fischer RJ, Sugden KD, Martin BD. Inhibition by methylated organo-arsenicals of the respiratory 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenases. J Organomet Chem (2009) 694:973-980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.12.028 50. Inhibition of the α‐ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex by the myeloperoxidase products, hypochlorous acid and mono‐N‐chloramine - Jeitner - 2005 - Journal of Neurochemistry - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ftr/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02868.x [Accessed February 20, 2025] 51. Pirrung MC, Nauhaus SK, Singh B. Cofactor-Directed, Time-Dependent Inhibition of Thiamine Enzymes by the Fungal Toxin Moniliformin. J Org Chem (1996) 61:2592-2593. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo950451f 52. Humphries KM, Yoo Y, Szweda LI. Inhibition of NADH-linked mitochondrial respiration by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Biochemistry (1998) 37:552-557. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi971958i 53. Park LC, Gibson GE, Bunik V, Cooper AJ. Inhibition of select mitochondrial enzymes in PC12 cells exposed to S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine. Biochem Pharmacol (1999) 58:1557-1565. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00247-6 54. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci (2005) 360:2335-2345. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1764 55. Gibson GE, Park LC, Sheu KF, Blass JP, Calingasan NY. The alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in neurodegeneration. Neurochem Int (2000) 36:97-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00114-x 56. Gibson GE, Feldman HH, Zhang S, Flowers SA, Luchsinger JA. Pharmacological thiamine levels as a therapeutic approach in Alzheimer's disease. Front Med (2022) 9:1033272. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1033272 57. Hakim AM, Carpenter S, Pappius HM. Metabolic and histological reversibility of thiamine deficiency. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab (1983) 3:468-477. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.1983.73 58. Hazell AS, Rao KV, Danbolt NC, Pow DV, Butterworth RF. Selective down-regulation of the astrocyte glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST within the medial thalamus in experimental Wernicke's encephalopathy. J Neurochem (2001) 78:560-568. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00436.x 59. Ke Z-J, Gibson GE. Selective response of various brain cell types during neurodegeneration induced by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. Neurochem Int (2004) 45:361-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2003.09.008 60. Barclay LL, Gibson GE, Blass JP. Impairment of behavior and acetylcholine metabolism in thiamine deficiency. J Pharmacol Exp Ther (1981) 217:537-543. 61. Karuppagounder SS, Xu H, Shi Q, Chen LH, Pedrini S, Pechman D, Baker H, Beal MF, Gandy SE, Gibson GE. Thiamine deficiency induces oxidative stress and exacerbates the plaque pathology in Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurobiol Aging (2009) 30:1587-1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.12.013 62. Gibson GE, Feldman HH, Zhang S, Flowers SA, Luchsinger JA. Pharmacological thiamine levels as a therapeutic approach in Alzheimer's disease. Front Med (2022) 9: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1033272 63. Gibson GE, Hirsch JA, Cirio RT, Jordan BD, Fonzetti P, Elder J. Abnormal thiamine-dependent processes in Alzheimer's Disease. Lessons from diabetes. Mol Cell Neurosci (2013) 55:17-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2012.09.001 64. Héroux M, Raghavendra Rao VL, Lavoie J, Richardson JS, Butterworth RF. Alterations of thiamine phosphorylation and of thiamine-dependent enzymes in Alzheimer's disease. Metab Brain Dis (1996) 11:81-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02080933 65. Butterworth RF, Besnard AM. Thiamine-dependent enzyme changes in temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Metab Brain Dis (1990) 5:179-184. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00997071 66. Mastrogiacoma F, Lindsay JG, Bettendorff L, Rice J, Kish SJ. Brain protein and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol (1996) 39:592-598. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410390508 67. Gibson GE, Zhang H, Sheu KF, Bogdanovich N, Lindsay JG, Lannfelt L, Vestling M, Cowburn RF. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in Alzheimer brains bearing the APP670/671 mutation. Ann Neurol (1998) 44:676-681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410440414 68. Albers DS, Augood SJ, Park LC, Browne SE, Martin DM, Adamson J, Hutton M, Standaert DG, Vonsattel JP, Gibson GE, et al. Frontal lobe dysfunction in progressive supranuclear palsy: evidence for oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment. J Neurochem (2000) 74:878-881. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740878.x 69. Alzheimer's disease is associated with disruption in thiamin transport physiology: A potential role for neuroinflammation - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35750148/ [Accessed February 20, 2025] 70. Gibson GE, Feldman HH, Zhang S, Flowers SA, Luchsinger JA. Pharmacological thiamine levels as a therapeutic approach in Alzheimer's disease. Front Med (2022) 9: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1033272 71. Rao VLR, Richardson JS, Butterworth RF. Decreased activities of thiamine diphosphatase in frontal and temporal cortex in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res (1993) 631:334-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(93)91554-6 72. Gibson GE, Feldman HH, Zhang S, Flowers SA, Luchsinger JA. Pharmacological thiamine levels as a therapeutic approach in Alzheimer's disease. Front Med (2022) 9:1033272. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1033272 73. Burke Neurological Institute Receives a $45 Million NIH Grant to Study a Vitamin B1 Precursor for Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease in Multi-center Clinical Trial. Burke Neurol Inst https://burke.weill.cornell.edu/gibson-lab/impact/news-articles/burke-neurological-institute-receives-45-million-nih-grant-study [Accessed February 20, 2025] 74. Shen XM, Li H, Dryhurst G. Oxidative metabolites of 5-S-cysteinyldopamine inhibit the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex: possible relevance to the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Vienna Austria 1996 (2000) 107:959-978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007020070045 75. Schmidt S, Stautner C, Vu DT, Heinz A, Regensburger M, Karayel O, Trümbach D, Artati A, Kaltenhäuser S, Nassef MZ, et al. A reversible state of hypometabolism in a human cellular model of sporadic Parkinson's disease. Nat Commun (2023) 14:7674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42862-7 76. Gibson GE, Kingsbury AE, Xu H, Lindsay JG, Daniel S, Foster OJF, Lees AJ, Blass JP. Deficits in a tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme in brains from patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Int (2003) 43:129-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00225-5 77. Mizuno Y, Matuda S, Yoshino H, Mori H, Hattori N, Ikebe S. An immunohistochemical study on alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol (1994) 35:204-210. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410350212 78. Zagare A, Preciat G, Nickels SL, Luo X, Monzel AS, Gomez-Giro G, Robertson G, Jaeger C, Sharif J, Koseki H, et al. Omics data integration suggests a potential idiopathic Parkinson's disease signature. Commun Biol (2023) 6:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05548-w 79. Schmidt S, Stautner C, Vu DT, Heinz A, Regensburger M, Karayel O, Trümbach D, Artati A, Kaltenhäuser S, Nassef MZ, et al. A reversible state of hypometabolism in a human cellular model of sporadic Parkinson's disease. Nat Commun (2023) 14:7674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42862-7 80. Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Molina JA, Hernánz A, Fernández-Vivancos E, de Bustos F, Barcenilla B, Gómez-Escalonilla C, Zurdo M, Berbel A, Villanueva C. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of thiamine in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett (1999) 271:33-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00515-7 81. Costantini A, Fancellu R. An open-label pilot study with high-dose thiamine in Parkinson's disease. Neural Regen Res (2016) 11:406-407. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.179047 82. Costantini A, Pala MI, Grossi E, Mondonico S, Cardelli LE, Jenner C, Proietti S, Colangeli M, Fancellu R. Long-Term Treatment with High-Dose Thiamine in Parkinson Disease: An Open-Label Pilot Study. J Altern Complement Med N Y N (2015) 21:740-747. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0353 83. Bohnen NI, Albin RL. The Cholinergic System and Parkinson Disease. Behav Brain Res (2011) 221:564-573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.048 84. Bohnen NI, Yarnall AJ, Weil RS, Moro E, Moehle MS, Borghammer P, Bedard M-A, Albin RL. Cholinergic system changes in Parkinson's disease: emerging therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol (2022) 21:381-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00377-X 85. Sasa M, Takemoto I, Nishino K, Itokawa Y. The Role of Thiamine on Excitable Membrane of Crayfish Giant Axon. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) (1976) 22:21-24. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.22.Supplement_21 86. Nghiem H-O, Bettendorff L, Changeux J-P. Specific phosphorylation of Torpedo 43K rapsyn by endogenous kinase(s) with thiamine triphosphate as the phosphate donor. FASEB J (2000) 14:543-554. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.14.3.543 87. Parkhomenko IM, Strokina AA, Pilipchuk SI, Stepanenko SP, Chekhovskaia LI, Donchenko GV. Existence of two different active sites on thiamine binding protein in plasma membranes of synaptosomes. Ukr Biokhimichnyi Zhurnal 1999 (2010) 82:34-41. 88. Parkhomenko YuM, Vovk AI, Protasova ZS, Pylypchuk SY, Chorny SA, Pavlova OS, Mejenska OA, Chehovska LI, Stepanenko SP. Thiazolium salt mimics the non-coenzyme effects of vitamin B1 in rat synaptosomes. Neurochem Int (1999) 178:105791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2024.105791 89. Parkhomenko YuM, Pavlova AS, Mezhenskaya OA. Mechanisms Responsible for the High Sensitivity of Neural Cells to Vitamin B1 Deficiency. Neurophysiology (2016) 48:429-448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11062-017-9620-3 90. Von Muralt A. The role of thiamine (vitamin B1) in nervous excitation. Exp Cell Res (1958) 14:72-79. 91. Von Muralt-(Bern) A. "Thiamine and Peripheral Neurophysiology.," In: Harris RS, Thimann KV, editors. Vitamins & Hormones. Academic Press (1947). p. 93-118 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0083-6729(08)60807-9 92. Minz, B. Sur la liberation de la vitamine B1 par le trone isole de nerf pneumogastrique soumis a l'exitation electrique. CRSoc Biol (1938) 127:1251-1253. 93. Waldenlind L, Elfman L, Rydqvist B. Binding of thiamine to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Torpedo marmorata and the frog end plate. Acta Physiol Scand (1978) 103:154-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06202.x 94. Ollat H, Laurent B, Bakchine S, Michel B-F, Touchon J, Dubois B. Effets de l'association de la Sulbutiamine à un inhibiteur de l'acétylcholinestérase dans les formes légères à modérées de la maladie d'Alzheimer. L'Encéphale (2007) 33:211-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7006(07)91552-3 95. Nagata M, Sugimoto J. The Influences of Drugs on the Experimental Constipation of Mice treated with Atropine and Papaverine. J Kansai Med Univ (1973) 25:300-321. https://doi.org/10.5361/jkmu1956.25.3_300 96. Sorbi S, Bird ED, Blass JP. Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in Huntington and Alzheimer brain. Ann Neurol (1983) 13:72-78. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410130116 97. Naia L, Cunha-Oliveira T, Rodrigues J, Rosenstock TR, Oliveira A, Ribeiro M, Carmo C, Oliveira-Sousa SI, Duarte AI, Hayden MR, et al. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Protect Against Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Dysfunction in Huntington's Disease. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci (2017) 37:2776-2794. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2006-14.2016 98. Chang C-P, Wu C-W, Chern Y. Metabolic dysregulation in Huntington's disease: Neuronal and glial perspectives. Neurobiol Dis (2024) 201:106672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106672 99. Pose-Utrilla J, Martínez-Horta S, Macías-García D, Vázquez-Oliver A, Picó S, Ojeda-Lepe E, Castro M, Rivas-Asensio E, Pérez B, Iglesias T, et al. D013 Thiamine deficiency in CSF of Huntington's disease presymptomatic carriers evidences etiological relevance and value as predictive biomarker. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2024) 95:A39-A40. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2024-EHDN.88 100. Lim RG, Al-Dalahmah O, Wu J, Gold MP, Reidling JC, Tang G, Adam M, Dansu DK, Park H-J, Casaccia P, et al. Huntington disease oligodendrocyte maturation deficits revealed by single-nucleus RNAseq are rescued by thiamine-biotin supplementation. Nat Commun (2022) 13:7791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35388-x 101. Picó S, Parras A, Santos-Galindo M, Pose-Utrilla J, Castro M, Fraga E, Hernández IH, Elorza A, Anta H, Wang N, et al. CPEB alteration and aberrant transcriptome-polyadenylation lead to a treatable SLC19A3 deficiency in Huntington's disease. Sci Transl Med (2021) 13:eabe7104. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abe7104 102. Study on the Use of Thiamine and Biotin for Patients with Huntington's Disease. Eur Clin Trials Inf Netw https://clinicaltrials.eu/trial/study-on-the-use-of-thiamine-and-biotin-for-patients-with-huntingtons-disease/ [Accessed February 20, 2025] 103. Laforenza U, Patrini C, Poloni M, Mazzarello P, Ceroni M, Gajdusek DC, Garruto RM. Thiamin mono- and pyrophosphatase activities from brain homogenate of Guamanian amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and parkinsonism-dementia patients. J Neurol Sci (1992) 109:156-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510x(92)90162-e 104. Poloni M, Patrini C, Rocchelli B, Rindi G. Thiamin monophosphate in the CSF of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol (1982) 39:507-509. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1982.00510200049009 105. Jesse S, Thal DR, Ludolph AC. Thiamine deficiency in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2015) 86:1166-1168. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2014-309435 106. Mann RH. Impaired Thiamine Metabolism in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Its Potential Treatment With Benfotiamine: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature. Cureus 15:e40511. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.40511 107. Probert F, Gorlova A, Deikin A, Bettendorff L, Veniaminova E, Nedorubov A, Chaprov KD, Ivanova TA, Anthony DC, Strekalova T. In FUS[1−359]‐tg mice O,S-dibenzoyl thiamine reduces muscle atrophy, decreases glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta, and normalizes the metabolome. Biomed Pharmacother (2022) 156:113986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113986 108. Antonio Costantini's research works | American University of Rome and other places. ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/Antonio-Costantini-2004482521 [Accessed February 20, 2025] 109. Costantini A, Pala MI, Tundo S, Matteucci P. High-dose thiamine improves the symptoms of fibromyalgia. BMJ Case Rep (2013) 2013:bcr2013009019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009019 110. Eisinger J, Ayavou T. Transketolase stimulation in fibromyalgia. J Am Coll Nutr (1990) 9:56-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1990.10720350 111. Eisinger J, Plantamura A, Ayavou T. Glycolysis abnormalities in fibromyalgia. J Am Coll Nutr (1994) 13:144-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1994.10718387 112. Eisinger J. Metabolic Abnormalities in Fibromyalgia. Clin Bull Myofascial Ther (1998) 3:3-21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J425v03n01_02 113. Vitamin B1 abnormalities in persons with fibromyalgia, myofascial pain syndrome and chronic alcoholism. ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297350573_Vitamin_B1_abnormalities_in_persons_with_fibromyalgia_myofascial_pain_syndrome_and_chronic_alcoholism [Accessed February 20, 2025] 114. Mkrtchyan GV, Üçal M, Müllebner A, Dumitrescu S, Kames M, Moldzio R, Molcanyi M, Schaefer S, Weidinger A, Schaefer U, et al. Thiamine preserves mitochondrial function in a rat model of traumatic brain injury, preventing inactivation of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg (2018) 1859:925-931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.005 115. Boyko A, Ksenofontov A, Ryabov S, Baratova L, Graf A, Bunik V. Delayed Influence of Spinal Cord Injury on the Amino Acids of NO• Metabolism in Rat Cerebral Cortex Is Attenuated by Thiamine. Front Med (2018) 4: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00249 116. Voloboueva LA, Lee SW, Emery JF, Palmer TD, Giffard RG. Mitochondrial Protection Attenuates Inflammation-Induced Impairment of Neurogenesis In Vitro and In Vivo. J Neurosci (2010) 30:12242-12251. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1752-10.2010 117. Yamada Y, Kusakari Y, Akaoka M, Watanabe M, Tanihata J, Nishioka N, Bochimoto H, Akaike T, Tachibana T, Minamisawa S. Thiamine treatment preserves cardiac function against ischemia injury via maintaining mitochondrial size and ATP levels. J Appl Physiol (2021) 130:26-35. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00578.2020 118. Ikeda K, Liu X, Kida K, Marutani E, Hirai S, Sakaguchi M, Andersen LW, Bagchi A, Cocchi MN, Berg KM, et al. Thiamine as a neuroprotective agent after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation (2016) 105:138-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.04.024 119. Sheline CT, Choi EH, Kim-Han J-S, Dugan LL, Choi DW. Cofactors of mitochondrial enzymes attenuate copper-induced death in vitro and in vivo. Ann Neurol (2002) 52:195-204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10276 120. Tanaka T, Sohmiya K, Kono T, Terasaki F, Horie R, Ohkaru Y, Muramatsu M, Takai S, Miyazaki M, Kitaura Y. Thiamine attenuates the hypertension and metabolic abnormalities in CD36-defective SHR: Uncoupling of glucose oxidation from cellular entry accompanied with enhanced protein O-GlcNAcylation in CD36 deficiency. Mol Cell Biochem (2007) 299:23-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-005-9032-3 121. Nozaki S, Mizuma H, Tanaka M, Jin G, Tahara T, Mizuno K, Yamato M, Okuyama K, Eguchi A, Akimoto K, et al. Thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide improves energy metabolism and physical performance during physical-fatigue loading in rats. Nutr Res (2009) 29:867-872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2009.10.007 122. Turan MI, Siltelioglu Turan I, Mammadov R, Altınkaynak K, Kisaoglu A. The Effect of Thiamine and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Oxidative Liver Damage Induced in Rats with Cisplatin. BioMed Res Int (2013) 2013:783809. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/783809 123. Yapca OE, Turan MI, Cetin N, Borekci B, Gul MA. Use of thiamine pyrophosphate to prevent infertility developing in rats undergoing unilateral ovariectomy and with ischemia reperfusion induced in the contralateral ovary. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2013) 170:521-525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.07.027 124. Konopacka M, Rogoliński J. Thiamine prevents X-ray induction of genetic changes in human lymphocytes in vitro. Acta Biochim Pol (2004) 51:839-843. 125. Gorlova A, Pavlov D, Anthony DC, Ponomarev ED, Sambon M, Proshin A, Shafarevich I, Babaevskaya D, Lesсh K-P, Bettendorff L, et al. Thiamine and benfotiamine counteract ultrasound-induced aggression, normalize AMPA receptor expression and plasticity markers, and reduce oxidative stress in mice. Neuropharmacology (2019) 156:107543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.02.025 126. Nourian K, Shahsavani D, Baghshani H. Effects of lead (Pb) exposure on some blood biochemical indices in Cyprinus carpio: potential alleviative effects of thiamine. Comp Clin Pathol (2019) 28:189-194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-018-2814-2 127. Shin BH, Choi SH, Cho EY, Shin M-J, Hwang K-C, Cho HK, Chung JH, Jang Y. Thiamine attenuates hypoxia-induced cell death in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Mol Cells (2004) 18:133-140. Orthomolecular MedicineOrthomolecular medicine uses safe, effective nutritional therapy to fight illness. For more information: http://www.orthomolecular.org Find a DoctorTo locate an orthomolecular physician near you: http://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/v06n09.shtml The peer-reviewed Orthomolecular Medicine News Service is a non-profit and non-commercial informational resource. Editorial Review Board:

Jennifer L. Aliano, M.S., L.Ac., C.C.N. (USA)

Comments and media contact: editor@orthomolecular.org OMNS welcomes but is unable to respond to individual reader emails. Reader comments become the property of OMNS and may or may not be used for publication. To Subscribe at no charge: http://www.orthomolecular.org/subscribe.html To Unsubscribe from this list: http://www.orthomolecular.org/unsubscribe.html |

This website is managed by Riordan Clinic

A Non-profit 501(c)(3) Medical, Research and Educational Organization

3100 North Hillside Avenue, Wichita, KS 67219 USA

Phone: 316-682-3100; Fax: 316-682-5054

© (Riordan Clinic) 2004 - 2024c

Information on Orthomolecular.org is provided for educational purposes only. It is not intended as medical advice.

Consult your orthomolecular health care professional for individual guidance on specific health problems.